In the field of water and wastewater treatment, few chemicals are as widely used and as critical as Polyacrylamide (PAM). This versatile polymer is the backbone of efficient solid–liquid separation, helping operators transform turbid wastewater into clear effluent and manageable sludge.

However, with hundreds of PAM products on the market—cationic, anionic, and non-ionic—many engineers face the same challenge: Which PAM type is truly right for my water or sludge?

Choosing the wrong PAM does not simply reduce performance. It can lead to poor flocculation, excessive chemical consumption, higher operating costs, unstable effluent quality, and even regulatory risks. The key to success is not finding a “universal” product, but matching the PAM type precisely to the water chemistry and treatment objective.

This guide explains the working principles of PAM, compares the three main ionic types, and provides a practical decision framework to help you make the right selection with confidence.

How Polyacrylamide Works in Water Treatment

Before comparing PAM types, it is important to understand how PAM performs flocculation at a microscopic level. PAM does not work like simple chemical precipitation; instead, it relies on physical and electrochemical interactions.

Charge Neutralization

Most suspended particles in wastewater—such as organic matter, bacteria, and clay—carry a negative surface charge, which causes them to repel each other and remain suspended.

Cationic PAM, with positively charged functional groups, neutralizes these negative charges. Once repulsion is reduced, particles can aggregate and form flocs.

Polymer Bridging (The Core Mechanism)

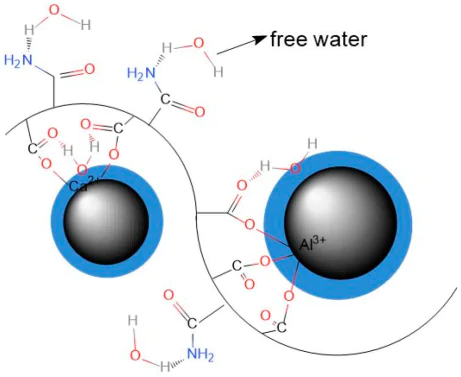

Polymer bridging is the most important flocculation mechanism for high–molecular-weight PAM.

Long PAM chains adsorb onto multiple particles at the same time, creating a three-dimensional network that binds particles together into large, fast-settling flocs. This mechanism applies to all PAM types, but is especially important for anionic and non-ionic PAM.

Sweep Flocculation (With Inorganic Coagulants)

When inorganic coagulants such as PAC or ferric salts are added, they form hydroxide precipitates that “sweep” particles out of suspension. PAM is often used afterward to strengthen these flocs, improving settling speed and floc stability.

Cationic Polyacrylamide (CPAM)

Key Characteristics

- Positively charged functional groups

- Medium to high molecular weight

- Available in a wide range of charge densities

Main Function

Charge neutralization + polymer bridging

Typical Applications

- Sludge dewatering (municipal and industrial)

- Wastewater with high organic content

- Paper manufacturing (retention and drainage aid)

Cationic PAM is the first choice for sludge dewatering, as biological sludge particles are strongly negatively charged. CPAM effectively releases bound water and forms dense flocs suitable for centrifuges, belt presses, and filter presses.

Water Chemistry Suitability

- Best performance in neutral to acidic conditions

- Reduced efficiency in strongly alkaline environments

Anionic Polyacrylamide (APAM)

Key Characteristics

- Negatively charged functional groups

- Very high molecular weight

- Low to medium charge density

Main Function

Strong polymer bridging

Typical Applications

- Mineral processing wastewater

- Sand washing and tailings treatment

- Drinking water clarification (with PAC or alum)

- Steel, metallurgy, and inorganic sludge treatment

Anionic PAM relies on its long molecular chains to bridge particles. It often requires multivalent cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺) or a primary coagulant to function effectively.

Water Chemistry Suitability

- Best in neutral to alkaline conditions

- Performs well in high-inorganic systems

Non-Ionic Polyacrylamide (NPAM)

Key Characteristics

- No ionic charge

- Very high molecular weight

- Stable across a wide pH range

Main Function

Pure polymer bridging

Typical Applications

- Acidic wastewater (e.g. acid mine drainage)

- High-salinity or high-conductivity water

- Oil–water separation

- Special chemical process wastewater

Non-ionic PAM is less affected by pH and salts, making it suitable for chemically harsh environments where ionic PAMs may lose efficiency.

How to Choose the Right PAM: A Practical Decision Guide

Step 1: Identify the Nature of Suspended Solids

- Organic / biological sludge → Cationic PAM

- Inorganic particles (sand, clay, minerals) → Anionic PAM

- Weakly charged or acidic systems → Non-ionic PAM

Step 2: Define the Treatment Objective

- Sludge dewatering → Cationic PAM

- Clarification and sedimentation → Anionic PAM (often with PAC)

- Filtration improvement → Depends on sludge type and shear resistance

Step 3: Check Key Water Parameters

- pH:

- Acidic → Cationic or Non-ionic

- Neutral to alkaline → Anionic

- Organic content (COD/BOD): High → Cationic

- Hardness: High calcium benefits anionic PAM performance

Step 4: Perform Jar Tests

Theory alone is not enough. Jar testing is essential to determine:

- Optimal PAM type

- Correct dosage

- Floc size, settling speed, and clarity

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Assuming all sludge behaves the same

- Ignoring pH and alkalinity

- Poor PAM dissolution and aging

- Excessive mixing that breaks polymer chains

Conclusion

There is no single “best” polyacrylamide—only the most suitable PAM for your specific water conditions.

- Choose cationic PAM for organic and biological sludge

- Choose anionic PAM for inorganic suspensions and clarification

- Choose non-ionic PAM for acidic, saline, or chemically complex systems

By combining proper chemical understanding with jar testing and real operating data, you can significantly reduce chemical consumption, improve treatment efficiency, and ensure stable, compliant operation.